Blog

Thirty years of digital development – seen through the eyes of someone who was there

Learn about 30 years of cybersecurity evolution, from early internet days and first hackers to modern threats like ransomware, emphasizing the need for constant vigilance.

One day in the early ’90s, I was flipping through the manual “Implementing UUCP over X.21.” I was determined to figure out how to send and receive emails from the outside world – something that wasn’t common back then.

The word “security” jumped out at me from one of the pages. My mind immediately shifted gears, and that same afternoon, I bought The Cuckoo’s Egg by Clifford Stoll—an astronomer turned cyber detective who uncovered a network of spies threatening national security. The story begins with a seemingly insignificant accounting error, which leads Stoll on a journey to track down a hacker who had infiltrated computers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

I devoured the book in no time, and without realizing it, I had just taken my first steps on what would become a long and exciting career path.

Denmark’s first hackers

Later that year, I attended a seminar on IT security led by Jørgen Bo Madsen, who was then the head of the Danish CERT at UNI-C. He captivated the audience with the story of Denmark’s first hackers: Jub Jub Bird and Sprocket.

Back at the office, I couldn’t resist trying out some of the techniques I’d learned on my boss. To this day, I’m grateful to him for encouraging my curiosity and pushing me to dive deeper into the world of IT security. At that time, “IT security” wasn’t really an established field. It was more a group of quirky IT people who, instead of following the manual, always thought outside the box: “What if we tried this instead…?”

The first Internet worm

As mentioned, this was when Internet access from your workplace was not a given, and it was naturally a crucial factor in choosing my new job. The Internet was something our customers talked about, and they wanted to know more about what this phenomenon could be used for and how to get connected.

Through this goldmine of knowledge, I learned that back in ’88, a man named Robert Tappan Morris set out to determine just how vast the Internet really was. After some coding and a single press of <Enter>, the first Internet worm—and the first DDoS attack—became a reality. It likely wasn’t his intention to create such a legacy, but it marked the true beginning of one of the most rapidly evolving industries we know today: cybersecurity.

As I recall those days, the general belief was that you were safe if you had antivirus software and a firewall. Antivirus programs didn’t captivate me much, but I was deeply involved in and closely followed the ongoing battle over which firewall technology was superior.

Mistrust Emerges

The choice was between Checkpoint’s Stateful Inspection technology, Cisco’s PIX—which was essentially just a box doing NAT—and finally, Raptor Eagle’s Proxy technology. It was a fierce battle between these manufacturers, fueled by more or less credible posts from vendors in various newsgroups.

Many people like me were deeply immersed in the technology and its possibilities. With my firewall, I could decide that everyone connected on the inside was good and everyone on the outside was bad. That was how it worked, and I was the “sheriff” keeping law and order in town.

The excitement of being able to communicate with people on the other side of the world was immense, and that was the driving force. Very few people thought about the “dark side” of this sudden technological globalization, and we all had to learn our own lessons.

I vividly remember my own “lightbulb” moment after installing an internet connection with a firewall for a customer. Feeling a bit self-satisfied, I proudly showed them the results. They could now point their Netscape browser to https://info.cern.ch while the firewall log scrolled down the screen with the familiar green (accept) and red (drop) lines.

The customer took a quick glance at the screen before leaving the room, only to return shortly after with their boss, exclaiming, “Look at that—those red lines are people trying to hack us. Good thing we got a firewall!”

It took a couple of hours to calm the boss down and reassure him that there was no need to contact the FBI, call the police, or disconnect the internet. But as I sat alone in my car later, reflecting on the day’s events, it struck me—the man was right, in principle. We had reached the next stage of the internet revolution: mistrust.

At the same time, we saw the commercialization of the Internet. Now, you didn’t need to build a skyscraper with a billboard on top to signal your size and influence. Anyone could create a nice website and send the same message about their business and achievements. Some companies even began experimenting with self-service and online commerce.

Another defining moment for me was when my bank put my account online. I clearly remember how horrified I was: How could they allow the “bad guys” direct access to my finances?

OK—maybe there was more to this than just antivirus and firewalls, and I had to start learning about technologies like encryption, authentication, and authorization.

The Emergence of Compliance, Risk, and Governance

I believe it was around this time that it started to become clear to me—and others—that this new, tightly connected world was highly vulnerable. It was also then that some recognized the need for a more systematic approach. A broader, more holistic view of the problem emerged, and new disciplines were introduced to address it.

“Holistic” and “systematic” were not words commonly associated with me, and others had to step in to try and save the world. This is how the GRC (Governance, Risk, and Compliance) field was born, and it wasn’t long before these professionals, with their heads held high and only one hand on the reins, rode through “security town” on their paper tigers.

The truth is, they were probably there all along. I was just too buried in the technical details to look up from my 14″ EGA screen. But it became clear that we needed to see the world differently and actually address the challenges head-on.

Even I had to acknowledge that security now had to be done for the sake of the business—not just because it was interesting. A formula that wasn’t part of my old playbook had to be learned, and it would become the foundation for all future security work:

Risk = Probability x Impact

The internet quickly spread and became the preferred platform for all kinds of shady experiments.

Viruses, defacement, and other shady activities are gaining strength on the internet

2001 was the year we became familiar with phenomena like the ILOVEYOU virus, Code Red, and Nimda—the latter becoming my nickname for a while thanks to a colleague’s creative wordplay with my initials.

Gradually, most companies effectively restricted access, making it impossible to reach vulnerable servers from the internet. Typically, only a web server and an email gateway were accessible externally. However, this didn’t diminish the creativity of certain individuals.

Defacement became the new topic of conversation, with many websites having their content replaced by more or less entertaining messages, often with political or propagandist motives. For example, The New York Times was forced to display pro-Syrian propaganda, and over 50 U.S. government websites were defaced by two Iranians in retaliation for the assassination of Iran’s military general Qasem Soleimani.

The innocence of hacking was gone; it was no longer done simply “because you could.” Now, there was a clear purpose behind it.

Stuxnet: political hacking

Hacking had evolved into a tool for activism, geopolitics, and even as a direct business model. This shift was exemplified by the story of Stuxnet, a highly complex computer worm discovered on the internet in 2010, believed to have been in development since at least 2005. Stuxnet was specifically designed to target and sabotage Iran’s nuclear program by manipulating the centrifuges used for uranium enrichment. It exploited multiple previously unknown vulnerabilities in the Windows operating system and Siemens Step7 software.

It’s widely accepted that the U.S. and Israel developed Stuxnet as part of a covert operation called Operation Olympic Games. This cyber approach was an alternative to attacking the facilities with bombers—an option that would have had more unpredictable and far-reaching consequences. Even today, people discuss how the code was smuggled into a network that supposedly had never been connected to the internet.

Phishing and Ransomware: The user as a tool

The issue of smuggling malicious code—or other deceptive information—into companies gained increased attention. Many of us have received emails from “Nigerian princes” offering large sums of money or from delivery services withholding packages due to customs fees.

The common factor in these attacks is that they try to trick the user into making a mistake. Whether it’s responding to an email, running a program, or clicking a link to “log in,” the goal is to exploit the user’s privileges to gain access to internal resources or information.

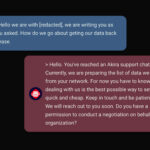

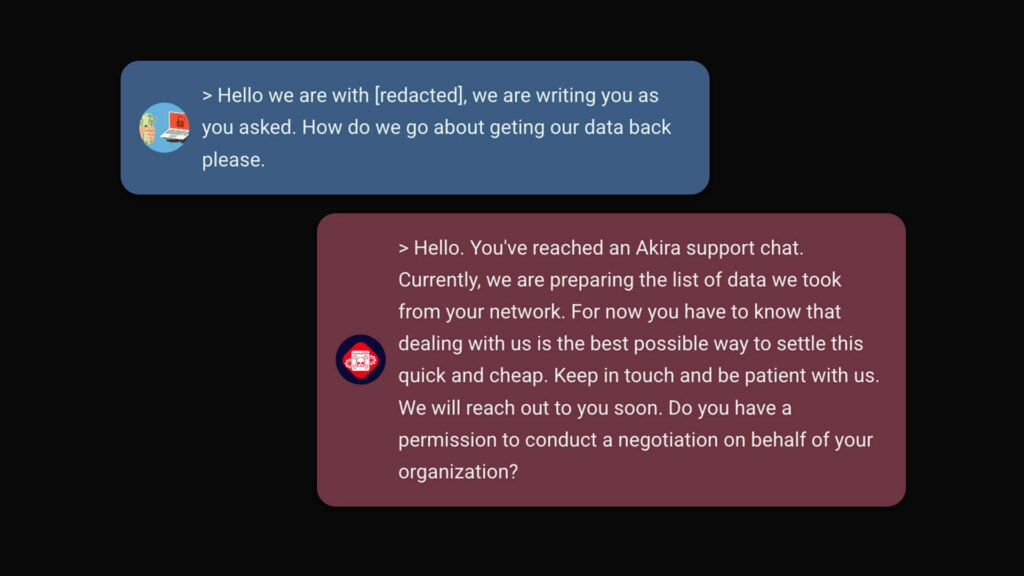

Phishing, as these types of attacks are called, is often the first step in a ransomware attack, which has become an industry in itself. The ransomware industry is now one of the most profitable and damaging forms of cybercrime, where malware encrypts a victim’s data and demands a ransom to restore access.

These attacks can cost businesses millions in ransom payments. For instance, ransomware attacks on large companies have resulted in ransom demands as high as $75 million, plus the costs of recovery, lost productivity, and the negative impact on the company’s reputation.

This type of attack has seen a significant increase in frequency and sophistication in recent years, as they can be launched cheaply. Although the success rate is low, the potential payoff is enormous if successful. Ransomware is a global threat, impacting organizations worldwide, and several companies have been destroyed because of it.

The Danish hosting company CloudNordic was one such example. All of their data—and their customer’s data—was encrypted, and reportedly, the company either couldn’t or wouldn’t pay the ransom. Shortly after, CloudNordic posted a brief explanation on their website along with a prominent “Apologies to our customers,” who were, of course, affected to varying degrees. Their phone lines were disconnected, and the company went bankrupt.

National and international authorities are working together to combat this form of cybercrime, but it’s an uphill battle. Many organizations profit heavily from it, and even state actors use these methods to fund other, more sophisticated activities.

NotPetya – an example

One such method involves finding alternative ways to smuggle malicious code into companies, which is exactly what happened to the renowned Danish company, Maersk. A Russian group compromised a server at a company that developed the popular Ukrainian accounting software, MeDoc. They infiltrated a software update being sent to customers, embedding the NotPetya malware within it. When users downloaded and installed the update, their systems became infected with NotPetya.

This attack was directly aimed at the Ukrainian population, with many businesses, banks, and shops brought to a standstill for an extended period. It was an attempt to destabilize the country and create widespread disruption.

Maersk, which also used this accounting software in its regional operations, was hit as well. Unfortunately, the malware spread throughout the company’s global network. NotPetya exploited a vulnerability in the Windows Server Message Block (SMB) protocol, known as EternalBlue, which was also used in the WannaCry attack earlier in 2017. This vulnerability allowed the malware to rapidly and automatically spread from one infected computer to others on the same network.

Before anyone realized what was happening, Maersk operations were paralyzed worldwide. Ships were anchored in ports across the globe, and trucks were stopped, blocking access to many major cities. It quickly became headline news, reaching everyday people who suddenly found themselves discussing and engaging with IT security.

Maersk managed to recover (which is an impressive story in itself), and they did the world a huge favor by being transparent about the incident. This, without a doubt, marked another defining moment in my career.

Maersk’s financial reports revealed that the incident had cost the company between 1.3 and 1.9 billion Danish kroner in lost revenue. Overnight, the conversation about IT security shifted from the basement server rooms to the executive boardrooms. Suddenly, it wasn’t just about firewalls and antivirus—it was about the survival of businesses.

For the first 25 years of my career, I felt like I was constantly shouting, “The wolf is coming!” But since that day in 2017, I’ve been saying, “I told you so!”

Who can we trust anymore?

The other side of the story is: Who can we trust? We’ve always been told to update our systems, but what happens when it’s our security software that gets compromised?

I think many people will remember the SolarWinds hack in 2020. It was the very software used to monitor the status of all our devices that ended up exposing critical information about entire infrastructures—and how they could potentially be compromised. This was another supply chain attack, and for many, it felt like the battle against the bad guys was becoming too overwhelming to continue.

I could go on with incidents like Log4J—where most people didn’t even know if they were vulnerable or to what extent. After all, how many of our systems rely on that library? Then there’s the Facebook data breach, where we still don’t fully understand the consequences. Not to mention the recent Crowdstrike incident, where even security software brought down many servers—some in the cloud, where you’d expect the top experts to be in control. These kinds of examples are becoming more frequent.

I’ve spent over 30 exciting years in what we call the “cybersecurity industry,” reality has consistently surpassed even the wildest imagination and at a speed, few could have predicted. I think it’s safe to say this “problem” isn’t going away anytime soon.

But remember Risk = Probability x Impact, which are two factors we can work with. We can reduce our risk significantly with a systematic approach and at least know where we stand.

I wish you all a safe and secure Cybersecurity Month!

Data breaches – Not a question of if, but when

Learn about the rising threat of ransomware and the need for robust data protection. Discover how Pure Storage safeguards data.

About the author

Niels Mogensen

Security Evangelist

As a Security Evangelist and “Techie by nature”, Niels Mogensen has great knowledge and interest in the soft aspects of IT security and to link these with the technological challenges – and opportunities. Niels Mogensen has been in the IT security industry for more than 25 years and therefore has an opinion on EVERYTHING – […]

Related